A while back I looked into whether or not SPList.ParentWeb really needs to be disposed: Is SPList.ParentWeb a Leak? The specific motivation was to investigate why SPList.BreakRoleInheritance() requires Dispose() on ParentWeb property, as seen in Roger’s Dispose Patterns by Example. I stand by my original conclusion that this advice generally does more harm than good, but thought it would be useful to discuss in a bit more detail.

Why dispose ParentWeb?

As I showed before, the code for SPList.ParentWeb works like this:

if (SPUtility.StsCompareStrings(this.m_Lists.Web.ServerRelativeUrl, this.ParentWebUrl)) return this.m_Lists.Web; if (this.m_parentWeb == null) this.m_parentWeb = this.m_Lists.Web.Site.OpenWeb(this.ParentWebUrl); return this.m_parentWeb;

In the vast majority of cases, the URLs will match and return the parent collection’s Web, which should not be disposed (unless, of course, you own it and know it is ready for disposal). Only in the exceptional case that the list’s ParentWebUrl indicates it doesn’t live with its parent collection will a new SPWeb be created. I believe it is this exception, rather than the norm, that leads to Roger’s suggestion that ParentWeb should be disposed.

On a curious and somewhat related note, SPListItem.Web doesn’t use ParentWeb:

public SPWeb get_Web()

{

return this.m_Items.List.Lists.Web;

}

Why BreakRoleInheritance()?

Though BreakRoleInheritance() has been singled out, the real culprit is an internal property:

private SPSecurableObjectImpl get_SecurableObjectImpl()

{

if (this.m_SecurableObjectImpl == null)

{

Guid guidScopeId = (Guid) this.m_arrListProps[0x22, this.m_iRow];

bool hasUniquePerm = guidScopeId != this.ParentWeb.RoleAssignments.Id;

this.m_SecurableObjectImpl = new SPSecurableObjectImpl(this.ParentWeb, this, ...);

}

return this.m_SecurableObjectImpl;

}

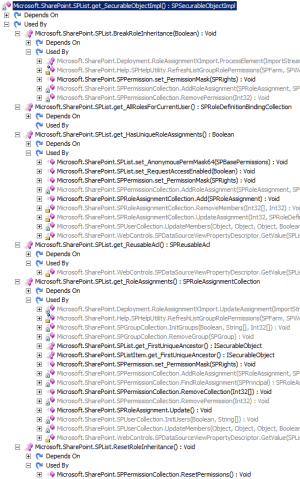

This property is then used in the implementations of several methods/properties from ISecurableObject:

- SPList.AllRolesForCurrentUser

- SPList.BreakRoleInheritance()

- SPList.HasUniqueRoleAssignments

- SPList.ResetRoleInheritance()

- SPList.ReusableAcl

- SPList.RoleAssignments

(Incidentally, SPSecurableObjectImpl is also used by SPWeb and SPListItem to implement that interface.)

So now we’re dealing with several more points of entry. For example, in

So now we’re dealing with several more points of entry. For example, in SPListItem:

public ISecurableObject get_FirstUniqueAncestor()

{

this.InitSecurity();

if (this.RoleAssignments.Id == this.ParentList.RoleAssignments.Id)

{

return this.ParentList.FirstUniqueAncestor;

}

if (!this.HasUniqueRoleAssignments)

{

return this.Web.GetFolder(this.m_strPermUrl).Item;

}

return this;

}

I could show several more obscure code paths with the same result, but the specifics are irrelevant. My point is that trying to figure out if SPList.ParentWeb has been referenced is a wasted effort.

What to do?

The way I see it, we have two options:

- Assume that

ParentWebis safe enough and if we have memory problems later we can investigate. - Assume that

ParentWebis leaky and figure out a safe way toDispose()it.

I’m satisfied with the former, but if you’re not — or if you have a circumstance where the ParentWebUrl comparison actually fails (please share) — then your code should check if it needs to dispose first:

SPWeb web = SPContext.Current.Web;

SPList list;

try

{

list = web.Lists["ListName"];

list.BreakRoleInheritance(true);

}

finally

{

if(list.ParentWeb != web)

list.ParentWeb.Dispose();

}

Or we can use an extension method:

public static void DisposeParentWeb(this SPList list)

{

if(list.ParentWeb != list.Lists.Web)

list.ParentWeb.Dispose();

}